o toki e pali

o toki e pali

cw; moku, jargon

Vivacious Verbs

NOUN li VERB

Particles are are a closed class including; li, e, en, pi, la, o, nanpa, anu

Puzzling Predicates - What is a predicate?

{John}(subject) {is sewing a bag}(predicate).

lipu pu

"Every sentence has a 'main verb'. This is the verb or other word used in this position, such as an adjective, noun or preposition. The main verb is normally the word that comes after the particle li."

lipu pu is neither the be all or end all of either the grammar of usage of toki pona and the language has evolved since then so people are constantly re-explaining and re-analysing toki pona as its used by people lon tenpo ni.

Puzzling Predicates Part 2 - Analysis Anarchy

A basic toki pona sentence looks like this:

X li Y [e Z]

the subject

- In the example above,

Xis the main character of our sentence, the subject

the predicate

- In the example above,

Yis this thing they are or are doing, the predicate

the direct object

- In the example above,

Zis the thing that the action is done to, the direct object

[...]

Prepositions are used to further describe the manner of the predicate.

[...]

The preverbs are special words that can change the meaning of the predicate in ways normal modifiers cannot. Unlike all other modification in toki pona, they occur before the predicate they are applied to.

This analysis is to allow for nouns and adjectives to be placed in the Y position. ona also indicates that that they call the initial position the subject.

But this causes the problem that only one word gets described as a predicate. What I have previously called a verb;

SUBJECT li PREDICATE

SUBJECT li [preverb] PREDICATE e DIRECT OBJECT

o sona: I cannot find explicit reference to if modifiers (MODIFIER) are included within subjects/predicates/direct objects or whether they are separate entities.

single capital letters (e.g. X) to represent any valid toki pona content word or phraseIn general, a phrase consists of a main content word, the head, and zero or more additional content words, the modifier(s).

Edit: Woooooops. kili pan Juli specified that all terms such as "subject" and "predicate" can refer to both an individual content word or a phrase and that phrases include a head and modifier(s).

First off - I am confused as to how you can have pre-verbs but no verb. In this analysis parts of speech and placement seem to be dislocated as suggested by;

content words

Literally every other word in toki pona is a content word with semantic meaning attached. Every content word can work like all of what is called "adjective", "adverb", "verb", "noun" in English. Some of these are part of special groupings that give them additional grammatical functions. All the words that aren't mentioned explicitly here are pure content words.

Perhaps this is the exception.

Secondly the fact that "predicate" can only refer to a content word or phrase makes it somewhat restrictive. The predicate is usually an area of a sentence. Remember these diagrams from Wikipedia;

As shown here and explained in the article; the predicate is/can be multiple word and can include many parts of speech. The opening to the Wikipedia article states;The term predicate is used in one of two ways in linguistics and its subfields. The first defines a predicate as everything in a standard declarative sentence except the subject, and the other views it as just the main content verb or associated predicative expression of a clause.

[edit:] This suggests the term is somewhat fluid but is often applied to a wider range of syntactic rather than the more narrow term "verb".

Puzzling Predicates Part 3 - Learners' Eyes

Constructive Commentary and Criticism - mi wile toki e toki ona.

It follows from labeling the “verb” of the sentence as the “predicate”, of course. Predicate is unambiguously better than verb, which I don’t believe I need to defend at this point? But here you go:

mi... ante pilin.

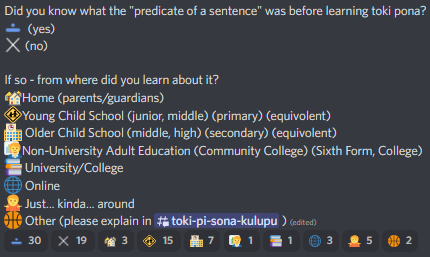

Learners often already have a concept of what a predicate is, which is reliably correct.

After disagreeing with jan Kekan San on this point (having not remembered it from either mainstream or special education [education for disabled children] I received in Britain) a snap poll of ma pona pi toki pona was held. The results were mixed but largely in our starry friends' favour - though with a large enough disparity that ~40% did not, suggesting understanding may be widespread by not not universal.

It may be the case that that 40% are having their notions of what "preposition" means shaped by jan Kekan San or toki pona as a whole - which could be problematic if the way its being used is not in line with its regular wider use.

One of the biggest learner struggles I see is conflating the position “verb” (as it is used among the community, intra-li-e-preds) with the function “verb” (informally: actions, not descriptions). Learners from an English background will point at “loje” in “soweli li loje” and say “adjective”, then be confused when you say it’s a verb. “li” looks like the copula “is” if you name that position “verb.” The trouble comes from analyzing Toki Pona words with English functions- you can produce analyses that let you put Toki Pona’s words into English’s positional/functional boxes, and those analyses will be valid, but they won’t necessarily mesh with a learner’s pre-existing understanding of English’s grammatical positions and functions.

jan Kekan San's analysis focuses mostly on English learners and minimising their misunderstandings. The "if it works it works" philosophy that teaching invokes is highly necessary and respectable. Not every course needs to be the be all and end all and if jan Kekan San is offering what ona offers as an introduction then its a good comprehensive non-linguistic introduction.

But toki pona is a language that is partially about rethinking language use - both on a semantic and syntactic level. An alternative point of view may hold that its good to bend learner's minds until they shatter and can reform stronger and more inquisitive.

Predicate doesn’t make a claim about function, only position, which is ideal.

This seems to mark an interest to move away from function as it is seen (noun/verb) and towards a position only understanding.

you’re trying to propose a consistent set of terminology for our teachers to use. We should choose as few new terms as possible, relying on a learner’s existing understanding of grammar as much as possible. Let them focus on the language, not the terminology surrounding it!

This point gets to the heart of a divide between grammaticians/linguists and teachers. Between the study of the language and the teaching thereof. Ideally we ought to be able to work together - with linguistics informing teaching. One goal of this lipu is to attempt to provide an agreeable basis and understanding of the grammar for teachers to utilise information from should they wish.

But, while its important not to overload jan pi kama sona - its also important to push them. Or more accurately; provide them with the tools to push themselves. As previously mentioned - toki pona is a language of linguistic self reflection.

That said, I don’t disagree with this analysis at all! Calling that position a verb isn’t necessarily wrong- it fits all the possible functions of a verb.

If this essay has given the false impression that anyone here actually disagrees then I hope that this will weka e ni. All writers li jan pi toki pona sama and agree on most things. The goal of this essay is to toki e ale and arrive at mutual conclusions.

Viva la Verb!

"Every sentence has a 'main verb'. This is the verb or other word used in this position, such as an adjective, noun or preposition. The main verb is normally the word that comes after the particle li."

This quote directly seems to indicate that something called the "main verb" is always present and that it can be a verb, noun, adjective or preposition

lipu pu also perhaps seems to use adjective to mean intransitive verb - seeing as transitive verbs are stated to exist but not intransitive.

It should be noted that lipu pu does not use content word theory, but instead classes words into nouns/verbs/adjectives (etc) in the dictionary. But it does show how words can be changed from one form into another.

This understanding is partially what evolved into the current verb-theory within content word theory. All parts of speech are interchangeable - any noun can become a verb and adjective and vice versa all three ways. But that doesn't stop nouns (nimi ijo), verbs (nimi pali) and modifiers (nimi kule) from existing. (modifiers = adjectives + adverbs).

A content word at the start of a sentence is still acting like a noun (indicating a physical or abstract object) - same with if it follows an e, en or preposition. A word after a head is still modifying it in some way - it applies kule to it. And a word slap bang in the syntactic middle of the sentence is indicating a state something is in or undergoing, either a continuous state or a state of change.

And this applies both to the pragmatic reality that the sentence is discussing AND to the syntactic and semantic reality within the language. Syntactically and semantically la, modifiers are not grammatically interchangeable with nouns and verbs due to the unique way each interacts with particles (such as pi, anu and en) as well as proper modifiers (names) (e.g. jan Lona). Nouns and verbs are quite similar in the way they can be heads for modifiers but the difference mostly occurs in the way they interact with pre-verbs which (as the name implies) interact with the verb as a verb.

An analysis using just head and modifier would be viable - but this misses the affect that verbs and nouns have across sentences. The way nouns can be either in the subject or object position depending on sentence construction (1), the way that verbs can become modifiers when not the predicate (new information) of the sentence (2) and the way that verbs can become nouns with their modifiers becoming their verbs and their subjects becoming their modifiers (3);

{C(noun)}(subject) li {kama[preverb] B(verb)}(predicate) tan[preposition] A(noun)

In longer texts, an understanding of these processes is key to building up contextual understanding via layering of information upon the same real world item/event/trait across multiple sentences, with the item/event/trait being discussed in multiple grammatical positions in order to allow different aspects of it to be explored. Use of the noun position to say what something is, use of modifier position to indicate distinguishing but happenstantial information and use of verb position to indicate a significant and notable state, action or change are linguistically typical uses of nouns, modifiers and verbs.

They are partially named for their pragmatic function (what they mean when they are translated into real life); that of being an item, a state, action or change, a decoration. But also partially because they fit the model of what a noun, verb and modifier look like in a positional particle driven grammar.

Verb and noun ought not to be bad words.

Self Criticism

As lipamanaka points out in ona's essay:

some speakers will use these rules reflexively on their own nasins and make claims about toki pona that aren’t true.

I am definitely guilty of this. I enjoy doing it for philosophical reasons and because the logic li pona pilin tawa mi, but it hinders my use of toki pona as a toki natural and possibly sona mi kin. I could do with a bit more of a naturalistic and descriptive mindset.

The full descriptivist/naturalist analysis of toki pona is not something I intend to toki about very heavily here. I eagerly await lipamanka's ongoing attempts at recording it. But I think adaptability to alternative nasins is a key skill to remember.

I came into this essay with a point to prove and I feel like I have made my case well having hyperfixated on writing it in an afternoon. But I've come away with greater appreciation for the view I was arguing against and less of a dislike for it. I've even disproven one of my own views.

One of my biggest fears is being misunderstood. pakala toki li ike e pilin mi. I write all I do not to push my view or argue over others, but that so that my toki li pakala ala.

References

lipamanka - lipu "descriptivism in toki pona" (28/11/22)

o pona!👋

CC-BY-SA-4.0

Comments

Post a Comment